[Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash]

“I feel melancholy sometimes, especially lately” said my friend as he leaned back in his chair. We were sitting in my backyard. The sun had just set and the sky had that lovely deep blue hue that appears for just a few brief moments as the day and the night fall into an embrace.

Melancholy. Hearing this word uttered out loud captivated me, perhaps a little too much as the silence between his statement and my reply stretched beyond what might be expected. And instead of asking follow up questions and voicing support, I exclaimed, “Oh, how wonderful!”

No, this certainly was not the right thing to say to a friend expressing his feelings. Fortunately, I was able to collect myself and quickly explain that I didn’t mean to make light of his melancholy state. I just appreciated him using this word as it gave me a deeper sense of the particular shade of sadness that at times comes over him. A meaningful conversation followed.

The word felt like a dear but long-gone traveler who finally returned to pay a visit.

The English language is fascinating in its dynamic richness. It is the lingua franca of the world; its influence and power are felt everywhere. Yet when it comes to how it is used to express emotions – especially the more painful emotions – in daily conversation, its potential is often squandered.

In casual conversation, one’s emotional distress is translated into a limited repertoire of statements. When talking about sadness, we might say that we are feeling down, sad, depressed, or upset. Then there is feeling angry, frustrated, overwhelmed, and the ubiquitous, “I am stressed out.”

These descriptors are incredibly basic; the emotions they are meant to convey are anything but. Take sadness. There is not one way to be sad. Sadness can feel heavy and oppressive, hopeless and impermeable, the kind that despotically demands submission from other emotions. Nothing else gets through when that type of sadness is in charge. It can also be very different; you might feel wistful, nostalgic, or disheartened. It can even have a hint of sweetness.

A few weeks ago I injured my hands. When a part of your body that you once took for granted refuses to work, the rude awakening is like having a bucket of ice-cold water thrown at you. I was jolted into humility and an unexpected gratitude practice for those parts of my body that do work. Thank you, eyes, for letting me see. Thank you, legs, for carrying me places. As part of my treatment, I entered physical therapy.

Anyone who has ever been in physical therapy knows it is an odd environment. In a culture that is all about privacy and space, where people apologetically say “excuse me” even when it is just the airflow that touched you as they were passing you by, physical therapy is a strangely communal space. You see people doing their exercises, you hear their grunts or verbal expressions of comfort or discomfort, you learn about what is going on with them as their physical therapists provide coaching and feedback.

You hear about and talk about physical pain in remarkably descriptive ways. Your physical therapist will not let you get away with the bland “it hurts.” Does your pain feel superficial or deep? Is it sharp? Sharp like a knife, or like a spike? Does it jab? Does it jolt? Does it burn like you are on fire or like you are close to the fire, and how close? Is it dull, like a bruise, or a toothache? Is there tingling or numbness? Is it cold or freezing? Steady or intermittent? Shooting, radiating, heavy? Are you miserable or just inconvenienced by it? If it hadn’t been for the fact that it was my pain we were talking about – a bit too close for comfort – I would have probably exclaimed again, “Oh, how wonderful!”

How wonderful to have at one’s disposal such rich language to not only describe but share one’s internal experience. How meaningful to have another person express a desire to understand that experience in such a deep way.

We need to expand the vocabulary we use to describe our emotions, especially those that challenge and distress us. You may wonder what is all the fuss about and what would this accomplish. Let’s explore this further.

My son was in 1st grade when the coronavirus pandemic swiftly upended his happy, predictable world. A few weeks into the increasingly miserable Zoom classroom experience, the conversation about how he has been doing went like this:

“How are you feeling?”

“I’m not feeling good, mom.”

“Can you describe how you feel?”

“Yeah, I feel bad.”

“Sweetie, you know how when you draw with crayons, you have all these different shades of the same color and you don’t draw with just one crayon? Feelings are like that too; they rarely are just one shade. Feeling bad can mean a lot of things. How else would you describe what you are feeling?”

“Hmm, ok, I would say I feel very bad.”

This did not go as planned. I tried to use other analogies and that helped some. (The weather analogy is a good one. I learned that his inner weather was not just heavy rain, but some good-sized hail too). He simply did not have the language to make sense of what he was going through. It meant confusion for him (and a temporary increase in tantrums). It also meant that I had a harder time knowing how to respond and help.

Clearly understanding the emotional experience you are having is a critical step toward distilling the meaning and wisdom (yes, wisdom) it contains. When you are feeling something, your limbic system – the part of the brain we share with other mammals – becomes activated. The limbic system is the center of emotion. If the experience is distressing and intense enough, the limbic system produces the fight/flight/freeze response. We are all familiar with the experience of having a surge of emotion and not being very logical in those moments. This is because the limbic system can overpower the newest part of our brain, the neocortex, which is all about reasoning, logic and intentional behavior.

It makes evolutionary sense to have the neocortex not be in charge when the limbic system detects a threat. If our brains had us indulge in a careful analysis of what steps should be taken when getting attacked by a lion in the savannah, our human species would not be here.

The downside is that because our brains don’t distinguish between lions and angry spouses or looming deadlines, we can get quite reactive when we are emotional even when there is no actual threat to our survival. If in those moments we can acknowledge what we are feeling AND turn on that lovely neocortex of ours to make more sense of what is going on, self-awareness can guide us in meaningful ways. Not only do we gain a greater sense of clarity, we get to connect with others by giving them a clearer window into what is happening with us. And we all know that empathy and connection have an analgesic effect.

Science shows this to be true. A study conducted in 2007 by Matthew D. Lieberman, UCLA professor of psychology, revealed that putting feelings into words makes sadness, anger and pain less intense. It calms the limbic system down. As the intensity decreases, it allows for curiosity about the experience to emerge. This is where we can learn about what has given rise to feeling a particular way, what it might say about what matters to us, and what we need to do about it. Thus, while there can be no wisdom without tapping into our emotions, there is work that must be done to distil their wisdom. In the raw, “unprocessed” form, they are fuel for the fight/flight/freeze response and might end up taking us down some treacherous paths.

When folks tell me that they have never tried psychotherapy but don’t think it is for them, they often say something like this: “What is the use of having someone ask me in a sympathetic tone, ‘how does this make you feel?’“ There is plenty of use! Identifying and sharing our feelings makes us happier, less reactive, and more intentional in the pursuit of a life that feels congruent with our values. And of course, there is more to psychotherapy than exploring how we feel.

A year into the pandemic, my son, now a 2nd grader, came back from school one day and we engaged in a familiar exchange.

“How was your day, honey?”

“Good.”

“Can you tell me more about what good means?”

“It was actually a bunch of things. It was emotional during recess. We played soccer and you know how badly I always want to score. My excitement kept climbing and so did my fear, and then we finally scored, and I felt really happy. So yeah, it was good.”

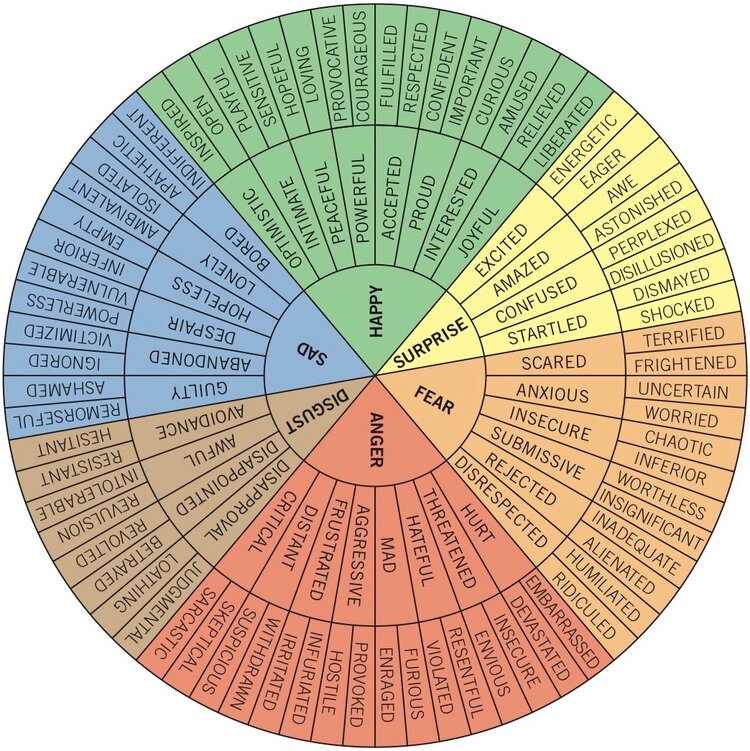

We are getting somewhere. One of the tools I had shown him – and which I love using with people of all ages – is the emotion wheel. There are many versions out there but they all tend to center around these primary emotions: fear, anger, joy, sadness, disgust, and surprise.

I would encourage you to study this wheel and get in the habit of describing your emotional experiences with greater accuracy and detail. It can be helpful to journal, especially if you find it difficult to be vulnerable with others. Remember, though, that the ultimate goal is to be able to share your experiences with trusted others and create the opportunity for connection and support.

Mindfulness is another practice that is known to increase our emotional literacy. It strengthens our capacity to observe the internal weather of our minds with curiosity and without judgment. You can start right now by spending a few minutes observing your breath. It is a simple but profound practice.

Today I am feeling lighthearted. Not sad, not happy. A little scattered and unfocused which may have to do with the fact that the sun is shining and summer is here. Oh yes, now as I say it, I see that this is excitement. There is a very subtle undercurrent of anxiety stemming from the awareness of all the tasks that have not yet been accomplished and await my attention today. Taking a deep breath, I notice that my body is tense. Time to take a break from being in front of the computer.

So, how are you feeling?