In all my years of supporting expectant parents as they navigate their pregnancy, birth and parenting, finding the right health care providers, the right therapists, the right doula has been front and center for them, and for those of us who are advocates. We’ve created guides and lists, and even healthcare personality quizzes to help this process of matching those who seek care to those who need them. And amidst the checklists of cesarean rates, and where someone received their training, and what level NICU the hospital has, or the experience someone has with our health conditions, are the really important questions.

Universally, we look for the provider of care to be kind, compassionate, to be respectful, to trust us when we know what we need, or what our experience has been, to listen until we feel understood, and to be able to share information in ways that allow us to share in the decision-making. We want them to be unbiased, and to treat us fairly.

We might want privacy in our hospital rooms, but we don’t want to be invisible. We want to be seen as more than a number, especially in our most vulnerable moments.

Research has grown over the years to tell us how much relationship matters. Not just because it feels better to have someone with a warm bedside manner. But it actually results in better outcomes. We get better care from someone who has the capacity to BE all those qualities, authentically.

I’m working with the verb ‘be’ and not ‘do’, because it’s the personhood of the provider, who they actually are, and how they hold themselves in a state of calm, caring attention, that our brains can recognize. This “personhood” of the practitioner, not only puts us at ease, but also results in their increased capacity to deliver their best care.

Themes in the research on health care outcomes

Relationship–centered care is a movement in health care that is drawing on important insights into healing and the delivery of quality healthcare. Side by side, it’s been recognized that health care providers need more training to be Trauma-Informed, and that bias in healthcare is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity. The more we learn about stress, trauma, and healing, the more we understand what goes wrong and see the depth of harm that bias in healthcare causes, the more we see arrows pointing towards the source of solutions: The mind and behaviors of the people in the health care systems.

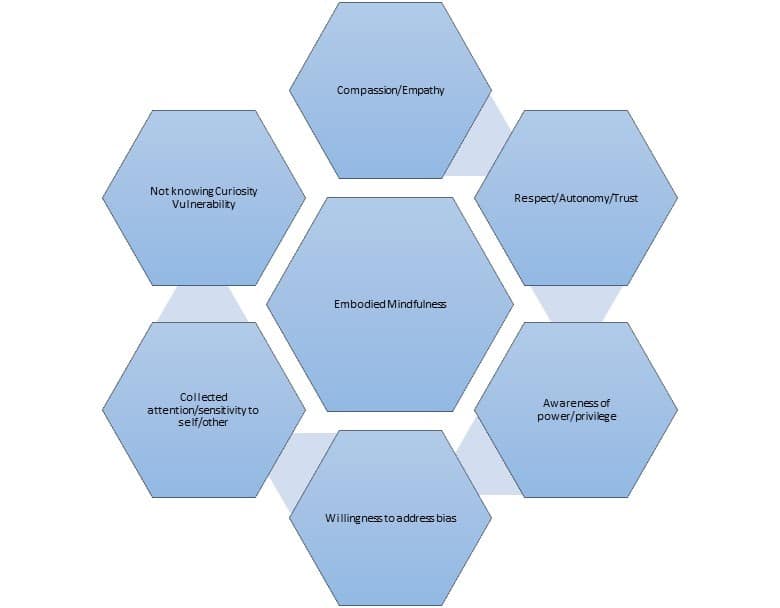

These 3 key frameworks for improving quality care: Relationship-Centered Care, Trauma-Informed Care, and Anti-bias frameworks, have key overlapping themes. They are: (Laing, 2019)

Where does mindfulness come into the picture? Mindfulness is described as paying attention, on purpose, nonjudgmentally. With mindful awareness, we can see ourselves clearly, and, having recognized patterns and behaviors, can choose what is more fitting in any particular moment.

Let’s just peek at a few of the reasons why a mind that is driven on automatic pilot is missing opportunities to give you the best care.

Fear and Stress Reactions as Drivers

You want your doctor or midwife to be attentive. To notice something important in your chart, or that you have a new symptom. This quality of attention is ideally, “clear –seeing.” Not too dull and relaxed that they are not paying attention, and not so anxious that they see everyone as a walking crisis waiting to happen. Exceptional health care is built on knowing when to let the body do its work, when to support it, when to turn to deeper levels of care and to skillfully collaborate with other experts when a situation warrants it. Too much intervention when it’s not necessary, or too little attention when it is, are the 2 sides to the coin of ineffective medicine.

Consider how clearly you think when you feel fear? Fear-based care is one that is more emotion-based than evidence-based. Anxiety, fear, and even trauma, are part of our human experience. Health care providers and mental health practitioners put themselves in the place to hold the pain and suffering of others, and put themselves, repeatedly, in the way of the most traumatic of human experiences. Their desire to help puts them in situations that we know impacts them. Without tools to be aware of the impact that fear and emotion have on their care, without self-care to manage the unknowns and the ‘what-ifs’, without a commitment to self-awareness and self-regulation, instead of a calm, clear, caring quality, providers can develop rigidity, and can be swept into reactive care, rather than responsive care.

We want providers who can make good, safe, medically sound decisions. These emerge from a mind not clouded by emotionally driven perceptions, but from being able to hold thoughts, emotions and reactions in a wise and spacious way. Physicians who began a meditation practice, had increased accuracy and better outcomes.

Empathic Distress vs Compassion

The world can weary us. Everyone I know has had times when they know they need a ‘news break.’ The tragedies we see on the news deplete us, and can haunt us. Providers of healthcare aren’t staying far on the sidelines. They are stepping into the middle of someone’s most painful life events.

Empathy is defined as ‘feeling with’. We feel another’s pain, often as deeply as if it were happening to us. Research shows that someone in an empathic response experiences similar stress reactions as if they were being harmed. Changes in blood pressure, heart rate, and brain wave patterns change. But when the subject was, in this case, a monk who practices compassion meditation, able to feel compassion, that warm, kind connection and sincere wish to relieve the suffering of another, the body not only calmed down but became generative, and experienced positive emotion. [1]

When a nurse comes in the room pushing pain medication in childbirth, far too often it’s not compassion, but their own empathic distress that is the driver. “I can’t deal with YOU being in pain, so I want to fix it (so I feel better.”)

When providers instead have the tools for managing this stress, and keep showing up for those in pain, they become our heroes. But it’s more than good intention. A good practitioner does a lot of work to make sense of what they encounter, and learn and practice daily, self-care that allows them to be fully present for our needs and to hold our pain and confusion. They have to have a way to hold their own pain and confusion, to know fear in skillful ways, so that their decision-making and their ability to reassure us when we feel shaky, is clear, wise, and authentic.

Relationships can be hard.

When we look at key skills needed for great health care, an environment of shared-decision-making is important across the disciplines. As receivers of care, this resonates with us. We want to be involved, to ask questions, to make choices that are right for us. Shared decision-making is not an easy task, however.

How easy is it for you to make sure that all of your decisions are shared with your partner? Maintaining respect, kindness and curiosity, even when you disagree? Even making a decision with a group of friends about where to go to dinner next Saturday can be rife with challenges!

Welcoming in other perspectives asks of someone to fend off the need to be right, to hold lightly all of the conditioning they have had to be an expert, a know-it-all, the first to raise their hand in class, to listen deeply when someone’s perspective needs to be heard and how to contribute important information.

Medical training not only often lacks training in these skills of relationship, but often drives these capacities out by the nature of the rigor and competition in the programs.

Providers for whom relationship matters, are consciously building back in the skills and practices that allow for the best connections with their patients.

Listening and Understanding

When I train even the most amazing providers, we always have an ‘aha’ moment when we do some practices around mindful listening.

Your therapists have received lots of training in listening, and when you experience being fully heard, there are lots of factors that they have cultivated in order to show up for you in this open, curious, way. We have lots of habits and conditioning around listening, and even holding full attention on any one thing can be difficult.

Think about your sitting in an hour long board meeting. Is your attention ever wandering off? Are you ever finding yourself thinking: “I know where this is going, I can tune out now?” or “what’s for lunch?” This is our brain’s default. It takes a deep commitment to train it to keep coming back to the present moment.

When you are being listened to, authentically, it takes deep practice and self-regulation on the part of the listener. The power of inquiry is built on the power of acceptance, curiosity and non-judgment, and patience to stick with the process until you experience being understood.

These qualities do come more readily to some than to others, but when the mind is under pressure or is experiencing unbuffered stress, our minds are designed to shut down to subtlety and focus on black/white thinking. We make quick decisions, see things as just one way or another, and our minds will cease to take in new information that doesn’t have a way to fit into our simplified way of thinking.

Stubbornness, for instance, in someone you know (maybe yourself) comes from not feeling relaxed enough, safe enough, to consider other alternatives.

The Healing Potential of Mindful Practitioners

We have to remember that our doctors, midwives, even our therapists are humans who are relating every moment to their own thoughts, emotions, and reactions. They have had training and conditioning not only to be a clinician by learning skills and techniques in school, they have had also, like you, had a lifetime of habits and conditioning about how to relate to one another.

Yes, it seems, that some providers naturally have a warm, kind manner. But we are recognizing that without ways to sustain this natural capacity, or ways to learn new ways of relating, providers are vulnerable to burnout and fall short of what we need of them.

Here is what one anesthesiologist had to say about training in compassion years after formal complaints were filed against him for comments he made to a woman and her partner during a cesarean:

“Over time, I have gradually re-conceptualized my role as that of a caring human being first and an expert second. That enabled me to be more humble and respectful, to listen patiently, to form more trusting relationships with my patients and to bring much greater compassion and humanity to the relationship.”[2]

Dr. Robin Youngson, who describes himself as being not naturally compassionate, has gone on to encourage other health care providers to train in ways that builds kindness, respect and compassion.

- Does your provider work in a supportive environment that creates opportunities for them to cultivate greater awareness, manage stress, and to grow personally and professionally?

- Do they have practices that support them, such as mindfulness meditation?

- Are the skills of compassion, awareness of implicit bias, respect and shared-decision-making something they consciously work on?

- Are they willing to say “I don’t have all the answers” and do they make room for you to trust your own experience?

- Do they embody kindness, respect, compassion, non-judgment, and curiosity?

Relationship-Centered Care doesn’t blur the boundaries of provider and patient it defines them as a space of caring. A provider more present for their own experience is more skillful to be present for yours and will create the space of safety you deserve.

Yes, there is a quality of vulnerability that we might be surprised by when a provider is transparent in ways we are not accustomed to. My wonderful family practice doctor is someone I’ve worked with for years. My daughter has a health condition and has had a number of hospitalizations. Every time, within the day, I get a call from her. And sometimes, she cries with me.

This is, for me, what a healing relationship looks like.

To learn more about Centered Care or to explore the tools mentioned to find a doctor or midwife for your maternity care, contact me.

[1] (Haakon G. Engen, September, 2015)

[2] (Byrom & Downe, 2015)

References

Beach MC, I. T. (2006). Relationship-Centered Care Research Network. Relationship-centered care. A constructive reframing. . J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S3–S8. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x.

Berila, B. (2016). Integrating Mindfulness into Anti-Oppression Pedagogy: Social justice in higher education. New York and London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Bloom, S. (1997). Creating Sanctuary: Towards the evolution of sane societies. New York and London: Routledge.

Byrom, S., & Downe, S. e. (2015). The Roar Behind the Silence: Why kindness, compassion and respect matter in maternity care. London: Pinter & Martin, Ltd.

Chinyere Oparah, J., Arega, H., Hudson, D., Jones, L., Oseguera, T., & Collective, B. W. (2018). Battling Over Birth: Black women and the maternal health care crisis. Praeclarus Press.

Creswell, J., & Lindsay, E. (2014). How Does Mindfulness Training Affect Health? A Mindfulness Buffering Account. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 401-407.

Epstein RM, S. R. (2011). The Values and Value of Patient-Centered Care. Annals of Family Medicine. Ann Fam Med, ;9(2):100-103. doi:10.1370/afm.1239.

Haakon G. Engen, T. S. (September, 2015). Compassion-based emotion regulation up-regulates experienced positive affect and associated neural networks. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Volume 10, Issue 9,, Pages 1291–1301, https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsv008.

Laing, K. (2019). WisdomWay Institute Publication. Can be used with proper attribution.

Lee, C. (2017). Awareness as a First Step Toward Overcoming Implicit Bias. Enhancing Justice: Reducing Bias 289 , https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2550&context=faculty_publications.

Livingstone, J. B. (2016). Relationship Power in Health Care: Science of behavior change, decision-making, and clinician self-care. Boca Raton, London, New York: CRC, imprint of Taylor & Francis Group.

Neff, K., & Germer, C. (2013). Self-Compassion in Clinical Practice. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY: IN SESSION,, Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jclp).

Santorelli, S. (2000). Heal Thyself: Lessons on mindfulness in medicine. Harmony.

Soklaridis, S., Ravitz, P., Adler Nevo, G., & Lieff, S. (2016 Vol. 3: Iss 1, Article 16). Relationship-centered care in health: A 20-year scoping review. Patient Experience Journal, Vol. 3: Iss 1, Article 16.

Wylson, A., & Chesley, J. (2016 Volume 19 Issue 1). The Benefits of Mindfulness in Leading Transformational Change. Graziadio Business Review | Graziadio School of Business and Management | Pepperdine University, https://gbr.pepperdine.edu/2016/04/the-benefits-of-mindfulness-in-leading-transformational-change/.